Considering the Slovenian history of the performing arts, one would hardly find anything close to an artistic movement in contemporary dance or theatre. One exception is the retro-garde movement Neue Slowenische Kunst and the following generation of theatre directors that made a practical and discursive change in the creation and production of theatre and introduced choreo-kinetic principles and approaches onto the stage in a fresh and daring way.

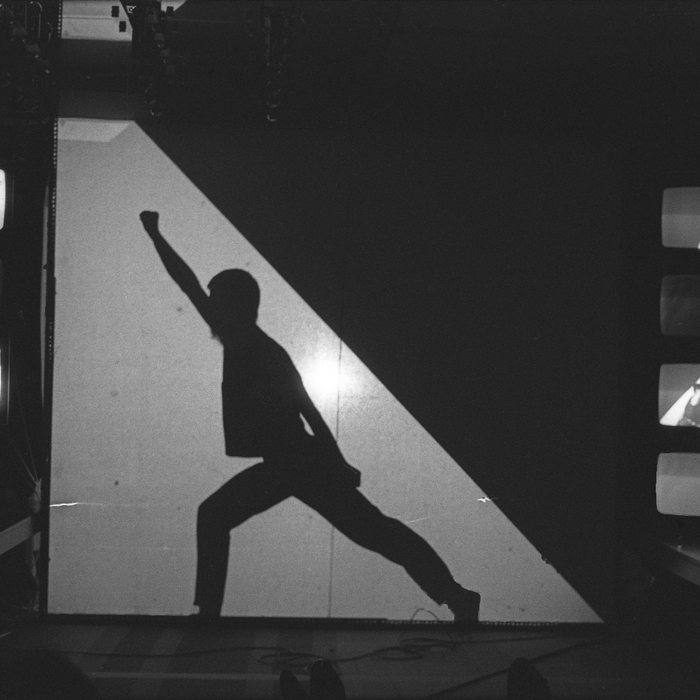

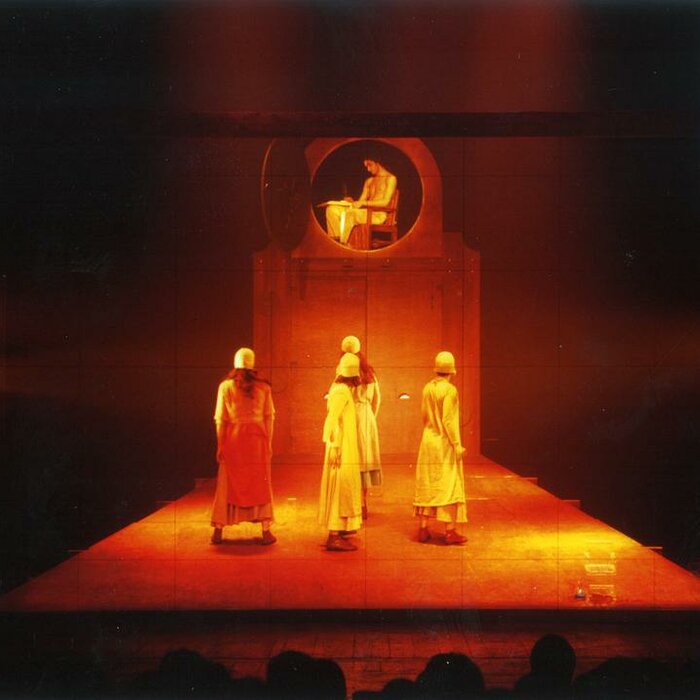

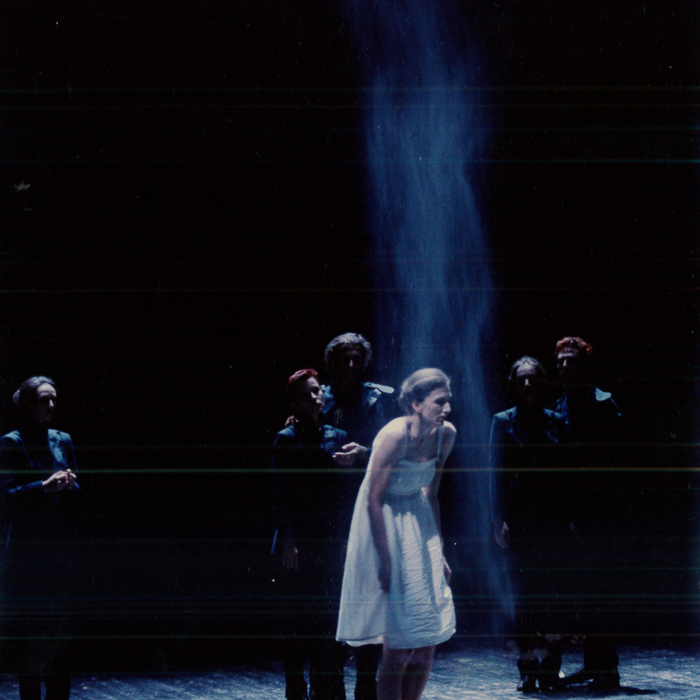

»In 1992, Eda Čufer, a theater theorist and dramaturge, now a well-known writer and historian of contemporary scenic arts, described a generation of theater directors (Matjaž Berger, Emil Hrvatin (now Janez Janša), Marko Košnik, Ema Kugler, Barbara Novaković Kolenc, Marko Peljhan, Vlado Repnik, Igor Štromajer) that came out of the changed artistic and cultural climate of the 1980s and was influenced by the permutations of the theatrical formation within the Neue Slowenische Kunst retro-garde movement (the Sisters of Scipion Nasica Theater, 1983–1987, the Cosmokinetic Theater Rdeči pilot, 1987–1990, and the Cosmokinetic Cabinet Noordung, 1900–1995–2045) with the collective name the Third Generation [Tretja generacija]. Aiming to apprise the Slovenian public of a certain qualitative aesthetic difference in the history and development of the scenic arts, this journalistic term, surprisingly, stuck, without any subsequent clarifications in terms of cultural history, theater studies, or genealogy. It can be speculatively understood as a differential descriptor used by Čufar to separate the then younger group of theater artists from those representatives of modernism (the second generation of directors) who had entered the Slovenian and Yugoslav theater arena with the aim to achieve artistic theatrical autonomy, especially vis-à-vis dramatic texts (plays) focused on Aristotelian mythos (plot) and ethos (character), and who had created a complex theatrical machine for confronting the literary public, instructed in the canonical examples of classical and modern dramatic chrono-topoi, with comprehensive theatrical interpretations of the world in their unpredictable, fresh, and bold repetitions (performances) by adding the otherwise lacking topical ‘nowness.’ While certain among the directors of that theatrical paradigm had distanced themselves from the bourgeois theater, where the public goes to see themselves reflected in the mirror of the stage, and had, in their experimental stages, radically interfered in the dramatic texts by promoting theatrical substitutes, the second generation’s theater was nonetheless founded above all on the right to provide a lucid mirror interpretive moment to which all the elements of the dramatic system are subordinated. In accordance with retro-utopian or contemporary artistic references and tendencies, the Third Generation subjected the public to a different theatrical machine, replacing the dramatic text with the directing text composed of a sequence of visual and choreo-kinetic actions, inhabiting the space of the performance with historical references (predominantly to historical artistic – but also political – avant-gardes), morphological differences, and other forms of physicality, and directing the attention of the public to processes that, unlike the interpretation of art, did not aspire to bring the public together in ‘finding common meanings,’ (Kunst 2006, 50–51) but aimed to confront it with a plurality of (relational) views in an agonistic dispute. The time in these works went from the current present moment of interpretive theater machines to analytical relations of physical and event presences and to referential networks of theater and other arts, expanding directing processes with curatorial principles of unpredictable time relations and parallels. In this theater, spectators were no longer competent interpreters, experts on metaphors that could act as critics in lieu of the general public, but curators of the view, narrators and editors of their own viewing process, readers of the medium and the act, expected to use their analytical competence to extend the performance beyond its ephemeral reception and establish that the theater is a liminal field between a performance and the process of reception, one that is prolonged into everyday reality. Which makes the view fundamentally uncertain and procedural« (Vevar and Založnik 2021, 40–42).

From Nika Arhar, Jasmina Založnik (ed.), Bodies ofm Dance, Aspects of Dance as Cultural, Political, and Art Work in Yugoslavia and After (Belgrade, 2024)